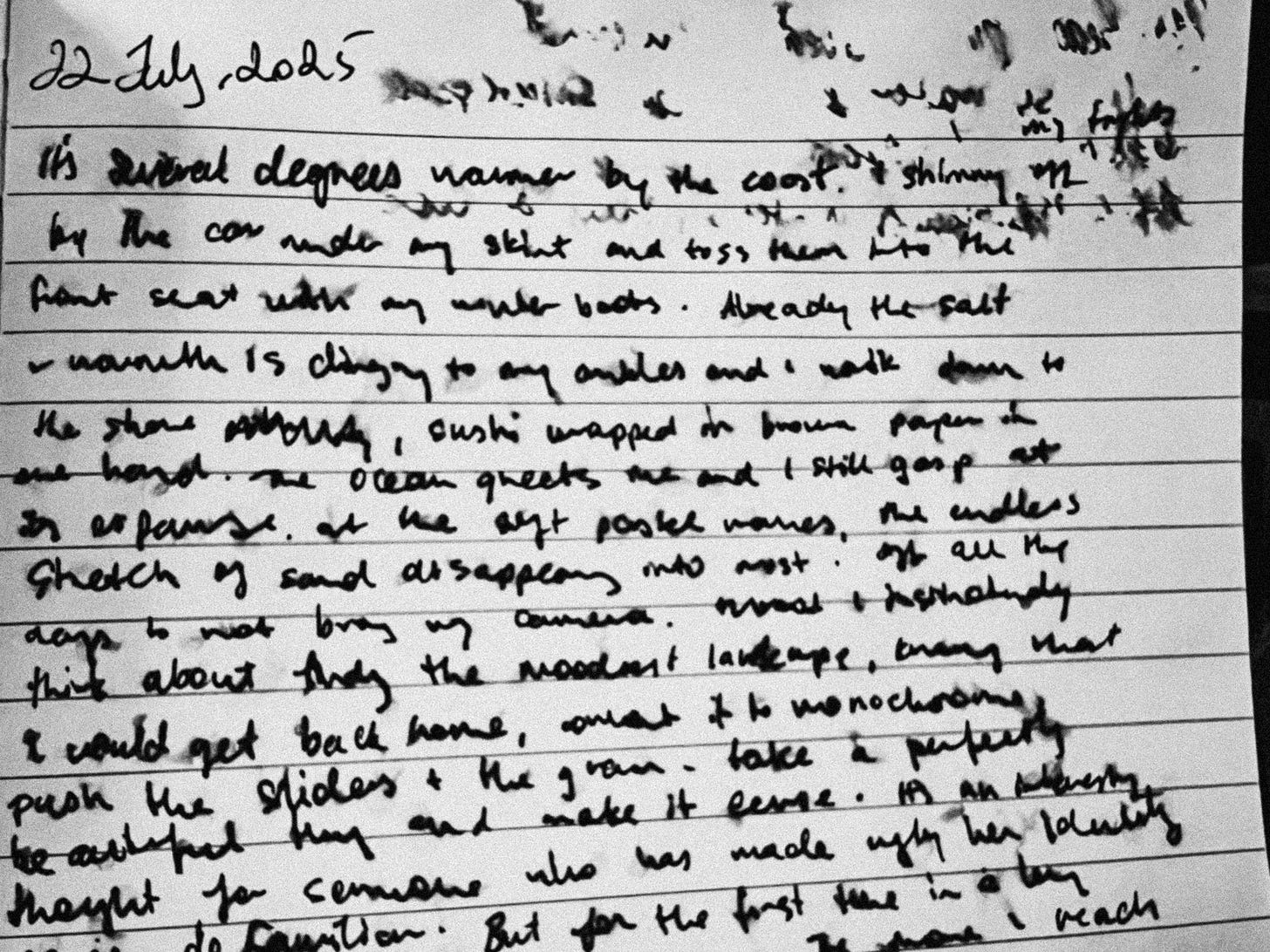

After parking the car at Peregian Beach, I shimmied my tights off under my skirt and tossed them into the front seat with my winter boots. The salt and warmth clung to my ankles as I walked down to the shore, skirt fluttering in the breeze. In my hand was a small bundle of sushi wrapped in brown paper. The ocean greeted me, and despite being a resident of paradise, I still gasped at the expanse—at the soft pastel waves, the endless stretch of sand disappearing into sea fog at the headland.

I immediately jumped up to photograph it, knowing full well that I would later convert it to monochrome, push the sliders and the grain to the extremes—take this perfectly beautiful vista and defamiliarise it. But then I took another guilty look at the horizon – this stunning day the universe had laid out before me – and sat back down.

When I began my Haunted Coastlines project in 2021, it was year two of the pandemic. My father had just died. My nervous system was a burned-out husk. I had made mood/gloomcore my identity and couldn’t reconcile what I didn’t believe I deserved—friends, a community, and the stunning natural beauty of my surrounds (which I had made my mission to destroy any perception of). Looking back, I’m pretty sure the only ghost I was stalking on those beaches was my own.

For years, fine-art printers have groaned when they saw me coming with my heavy blacks filling each frame, knowing that the print had to be crisp enough to make out whatever was lurking in the blur. I basked in pride when someone had to twist their neck to work out what they were looking at. But lately I have been faltering at the urge.

As a child, creating something “bad” or difficult to look at was my little act of rebellion—a way to subvert the impossible standards that I languished under in other areas of my life. I would deliberately colour outside the lines, choose the ugly crayons at the group table, scribble hard and fast, colours smudging under my wrist. As long as my art was bad, I was safe. And as long as I was invisible, no one would expect me to shine. No one would put my art on a pedestal and tell everyone how brilliant their daughter was and how she was destined for higher things. Making messy art allowed me to breathe.

Sitting on the warm sand, between mouthfuls of salmon and avocado, I realised that my creative practice has always pendulumed between this-needs-to-be-perfect and I-made-it-so-ugly-you'll-hate-it. And I began to wonder if it was sustainable. As I watched the tide ripple and recede, I thought about Mary Oliver’s words1:

Maybe our world will grow kinder eventually.

Maybe the desire to make something beautiful

is the piece of God that is inside each of us.

What did it mean for my artistic soul if I was lacking in that very desire?

In the past, the more I reached for gratitude – the more I allowed myself to cautiously love this life – the more I felt pulled between two worlds. All my ship's demons, taking me back to shore. This year, however, something has shifted. Each day we seem to descend further into horror, pulled away from our humanity, distracted by noise and division that keep us at war with each other.

And it feels like a wake-up call.

It feels like a choice.

I finished my lunch and turned again to the misty horizon. A shower passed over in spatters, blurring my words as ink pooled in blotches on the page, and I couldn’t help but laugh. Maybe I was destined to bask in ruined beauty after all.

It wasn’t long before the rain set in. I bundled up my books and pens, flattened the brown paper and slid it into my bag, dusted the sand off my skirt, and ran. By the time I reached my car, my hair and skin were soaked. I probably should have come earlier, or maybe checked the weather app and stayed home. But then I thought about fresh salmon melting on my tongue, avocado ripe and green, of soy and ginger and salt and rice and white sand and sea air that I got to witness for all of ten minutes, and the revelations that had settled over me.

Would it have made a difference if I’d stayed a second longer? An hour?

Who knows how long we have?

The next day, I returned with my camera, to hunt the sea mist again. Not because I'm trying to stay invisible in my own darkness, but because for once, I'm trying to stay visible in my own light.

With all the love and intention that I can muster.

Mary Oliver, “Franz Marc’s Blue Horses,” in Blue Horses (London: Corsair, 2018), 43.

I relate so well to that tension between wanting to rebel and wanting to shine. I love how you've expressed this.

Love this image Erica thank you for text peace of the peace Claire